History is replete with examples of gold being the ultimate asset in times of crisis and desperation, where time and time again, gold comes to the rescue and provides its holders with choice and freedom, choice and freedom that are not available to those who do not hold gold. This is not ancient but recent history,

In this article we will look at some examples of gold in crisis,

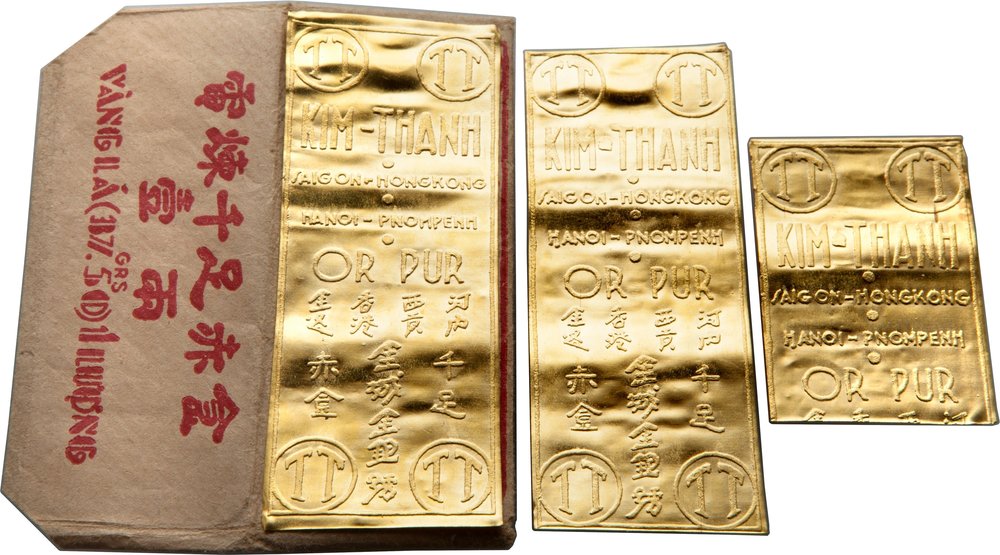

Distinctive slim gold bars from Vietnam’s Kim Thanh refinery, 1 tael

Distinctive slim gold bars from Vietnam’s Kim Thanh refinery, 1 taelFollowing the Vietnam War, the Fall of Saigon, and Vietnam’s reunification in 1976, the southern part of Vietnam experienced a mass exodus of people, driven by a crippled economy, government discrimination and forced departures. Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese fled to other parts of Asia over both land and sea, an exodus which peaked in 1978-1979.

Those refugees fleeing by

This gold payment

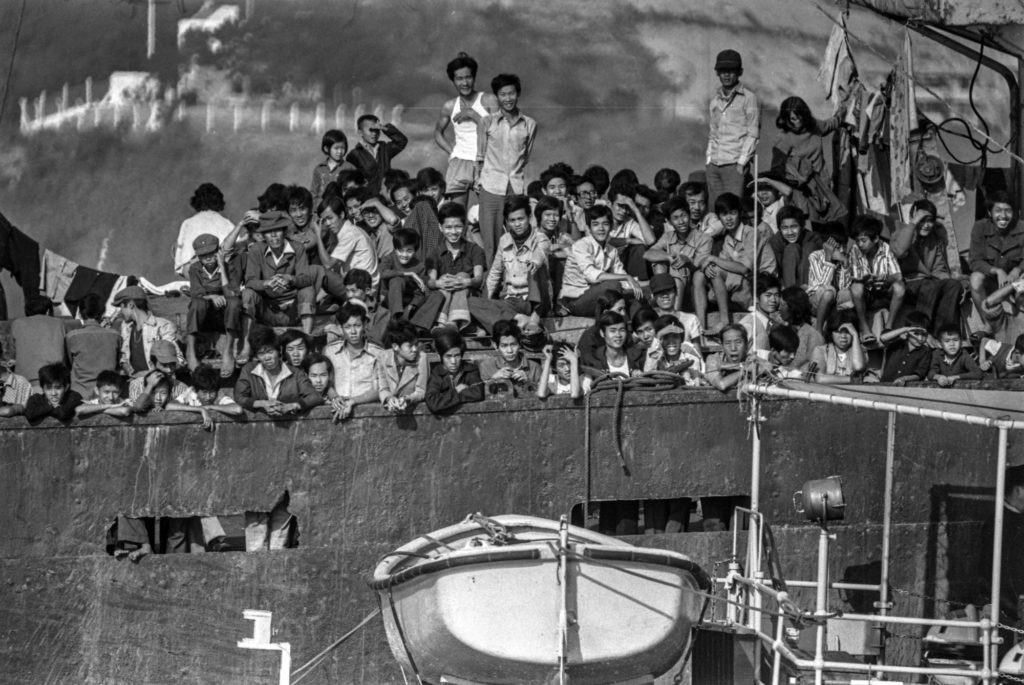

From Vietnam to Hong Kong – Skyluck, the ship that smuggled 2,600 refugees. Source: SCMP

From Vietnam to Hong Kong – Skyluck, the ship that smuggled 2,600 refugees. Source: SCMPAlthough some Vietnamese and

Refugees also took with them emergency money in the form of gold

Refugees from Vietnam who took huge risks sailing into the unknown to a better life could only do so because they had physical gold to buy safe passage, and because gold is a universal money that can be sold almost anywhere to help finance a new life abroad.

South Korea – Gold mobilization to pay external debt

As the Asian financial crisis spread to South Korea in late 1997 and torpedoed the country’s financial markets, it triggered a currency and banking crisis that decimated the Korean won and pushed the country to the verge of bankruptcy. Rapidly burning through its foreign exchange reserves and with international lenders circling, the government called in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in December 1997 with a multi billion rescue package to bail-out the country’s spiralling external debt. At that time the largest ever IMF bail-out, the rescue came as a massive blow to the Korean nation both economically and psychologically.

Embarrassed and at a loss to understand how a star Asian tiger economy could implode so quickly, the South Korean

Initiated by the Korean broadcast networks and the large Korean banks, and coordinated by the industrial conglomerates such as Hyundai, Daewoo and Samsung, the ‘love of nation’ and ‘national debt repayment’ campaign saw Korean citizens selling their gold, but at prices far lower than market value. The gold collected was then melted into gold bars and sold on the international gold market.

With gold held widely by Korean households in many shapes and forms, long lines formed outside the nation’s banks and collection points of Samsung, Daewoo and Hyundai as Koreans swarmed to sell everything from investment gold coins and bars to gold rings and gold bracelets, and from gold medals to gold trinkets. All to fix their ‘broken economy’. The items sold even included brides’ gold jewelry, gold

Kim Daejung, then president elect, donated his gold in

Kim Daejung, then president elect, donated his gold in And it wasn’t just ordinary citizens who took part in the campaign. Celebrities and politicians led by example. Korean baseball star Lee Chong-bum brought in 31 ounces of gold to his local bank in the form of gold trophies and medals. President-elect at the time Kim Daejung walked into a bank in Seoul donating a miniature golden tortoise and four golden good luck

”When I think of the patriotism, my eyes almost become wet with tears of appreciation. I promise that my new government will do its best to pull the country out of its current crisis.”

Running over four months from January to April 1998, the gold collection campaign collected 227 tonnes of gold worth $2.13 billion, with 165 tonnes alone collected in the

With gold playing a strong role in Korean society, South Korea’s population knew instinctively that in the midst of a dark economic crisis, only physical gold could help rescue their economy. And so they collectively

- Source, Bullionstar